When I show the card game Android: Netrunner off to my friends, it’s like trying to explain my favorite superhero comics. You play a hacker (that’s the “runner”) fighting a mega-corporation in a science fiction future.

I pull out my favorite runner cards and explain their personas: Chaos Theory, the teen genius with her Dinosaur-shaped computer; Valencia Estevez, the journalist and advocate for the disenfranchised; Leela Patel, the boxer and thrillseeker. They operate out of places like Cayambe, Mumbai, the moon. Like superheroes, they have different specialties that empower them as well as diverse backstories that make them relatable to all kinds of players.

Many of the runners are mixed race, and and almost half of them are women designed to avoid common objectifying tropes. Think of comic characters like Muslim-American Ms. Marvel, or Kingsway West, the Chinese gunslinger in a fantasy western—they’re visible pushes to include different types of people in traditionally “geek” spaces typically dominated by white guys.

When I first got into Netrunner two years ago, it felt like something special, and I’d hoped that its community would look different from that of collectible card games’ old guard, like Magic: The Gathering. I’ve met a lot of other Netrunner players since then who say this community is friendly, welcoming, and yeah, better than Magic’s. Yet when I look at my Netrunner friends, a majority of them are still twenty-/thirty-something white guys. (I’m a 28-year-old Vietnamese-American lady.) To their benefit, they’re with me in wondering why this is the case, why a game with such diversity within its lore doesn’t see it reflected in its player base.

My husband and I have a pattern around our board game play together: I bring home games that sound interesting to me, and he gets to comb through the rules and teach the both of us. When I brought home my first set of Netrunner cards, I remember understanding the basic premise of play: he, as the corporation, fills his servers with secrets, as I, the scrappy runner, gather the right programs to hack past his security measures to steal what they protect. We take turns playing both roles, but we’ve had our druthers from the start.

Netrunner is not a simple game. It’s got a lot of rules, many of which we didn’t fully get until we played with other people. That didn’t matter so much, because we understood the thrill at the core of the game: the run. When you’re hacking a server for the first time, you’re not sure if you’re going to get through. The corporation activates their security programs one-by-one—they can hurt you, stop you in your tracks, or even trace you back to where you live. You can beat the programs with your own or take the damage, persevering until you discover the secret at the heart of the server. More often than not at the end of a run, I release a breath I didn’t know I’d been holding, in either relief at having found a prize or resignation at having sprung a trap.

The tension built into a run is beautiful, and the vehicle for much of the game’s vivid storytelling. In runs, you can sneak into corporate headquarters, pull a bank heist, or be foiled by psychic operatives. There’s a world of scenarios that I want to explore with my friends, but I keep finding the game as a whole a hard sell, especially to other women who don’t have any collectible card game background.

“I think that the initial barrier to entry really is its LCG [living card game] format,” says game designer and critic Mattie Brice. “The people who play those sorts of games and what it takes to play those sorts of games... and some other aspects like heavy math and things.” Other card games like Magic, Pokémon, and Yu-Gi-Oh have their battling monsters, where there’s a lot of number juggling to resolve some kind of combat scenario. To the uninformed, Netrunner looks just like those other games, but with programs instead of monsters, and again, its players look the same.

Brice believes that representation in Netrunner’s lore helps its accessibility a little, but its cyberpunk influences are also a deterrent in a way that parallels its mechanics: “Its lore is steeped in in references to programming and hacking and... Neuromancer,” she says. I try to describe to potential players how Netrunner captures the feeling of programming without requiring any actual coding abilities, but for the people who find tech knowledge overwhelming or intimidating, Netrunner’s rule set feels comparably obtuse. Even after my multiple years of playing the game, there is a flow chart of actions that I haven’t committed to memory, and embarrassingly find myself googling on my phone when I’m trying to teach friends.

I see Netrunner’s storytelling and design as most effective in the kind of values common to the players it draws. Dan D’Argenio, Netrunner’s world champion of 2014 and webmaster for Stimhack, a Netrunner website and community hub, finds Netrunner’s character treatments helpful in drawing and keeping new players.

“There’s very little sexualization. This is a very appropriate game,” he says. “The general feeling is that the vast majority of the players are feminists, and not just feminists: pro-gay rights, not racists or [we] at least try to mitigate our racial predispositions/prejudices.”

When I was eleven, I played the Pokémon Trading Card Game (TCG). I taught myself how to play, and when I realized how quickly it bored my sister, I begged my dad to take me to a comic shop I knew had game nights. When I finally went, I was the youngest player there and sat across the table from a guy who looked twice my age. He spoke to me only as much as the game required and trounced my deck. I went home embarrassed.

My Pokémon experience fell very much in line with what your average person has come to expect, fairly or otherwise, from card game events. People tend to imagine them as taking place in the back of game stores with bad lighting and ventilation, attended by competitive dudes with varying levels of social ability and hygiene. Despite their reputation, these types of meetups are the center of community interaction for all collectible card games, and Netrunner is no exception. Though game stores are still the primary venues, Netrunner players are trying to change the conversation surrounding competitors’ behaviors.

"I think when people talk about Netrunner as opposed to [other communities], they talk about the lack of cutthroat-ness," D’Argenio says. He also posits that another part of the Netrunner community’s general maturity comes from an older average age of adults. “The under-20 presence in Netrunner is pretty non-existent,” he says. “We’ve lived in the real world long enough to interact with girls. We’re just mature enough, liberal enough, to sort of police ourselves in that regard.”

Lately much of D’Argenio’s work has been in helping to organize and acting as spokesman for the Android: Netrunner Pro Circuit (ANRPC), a fan-made infrastructure for supporting regional tournaments. D'Argenio believes in the ANRPC as a means of growing the game's community from the top down.

"The people who are likely to teach Netrunner and the people who are excited to teach Netrunner are...the competitive players," D'Argenio says. He believes that the visibility of high-level play brings more casual players into more focused competitive play, and makes those players more likely to grow their local communities.

Official Netrunner tournament prizes are typically cards and special, limited-edition play mats showing off game art. As the competitive scene has grown, however, cash prizes have started to appear. D’Argenio acknowledges the concern that monetary prizes, like those common in Magic events, invite more aggressive and hostile personalities into the competition scene: "Some people have an impression that it's because it's a larger prize purse, and I think a lot of people have a legitimate concern that ANRPC is a bad thing for the community." He mentions that even though the recent Warren, Michigan regional tournament included cash prizes, the atmosphere remained genial, and he has faith that players in the community can maintain their sportsmanship as the stakes get higher.

Despite these efforts, Netrunner’s competitive events still alienate some players. Brice attended a local store tournament in the San Francisco Bay Area, and has yet to attend another. “People’s turns when they’re competitive, they’re very fast. Like they speed through—they know exactly what to do,” she says. “If you’re newer or play more casually... you feel pressured to also go the same speed. It’s just generally not fun.”

Dominique Peters is a London-based player who’s followed the game for over a year now. She primarily plays with friends at work and with her partner, but went to her first organized event this year, a tournament held at a game cafe and bar. She was the only female participant. Though she didn’t experience any overt harassment, other players’ behavior still made her uncomfortable.

“It was actually the kind of level of, I guess, microaggressions. Just really, really small continuous things that happened all the time,” Peters says. She feels her opponents gave unsolicited deck advice, over-explained the mechanics as they played, questioned her about her gaming background as if to test her geek credentials, and asked if her boyfriend taught her how to play.

She says on the latter, “That’s a tricky one, because yes he did, but that’s not really relevant? Like, did your friend teach you to play? ...It’s kind of a non-question as far as I’m concerned, but it’s asked in a very particular way.” Her partner, another competitor at the tournament, experienced none of that line of questioning and treatment from other participants. By the end of the day, no one had spoken to Peters’ outside of her matches.

Brice experienced a similar wall of silence at her tournament. “People are unintentional about it, but there’s a lot of in-group-out-group type of dynamics that happen with games and gaming circles,” Brice says. “I think that people tend to only want to play with people who are on their same wavelength, and I think if you’re new or don’t look like them...it’s kind of harder for you to kind of be accepted into certain circles.”

My own tournament experiences have been positive in comparison, I think in large part due to the efforts of the store I attend. I started playing Netrunner with strangers at Labyrinth Puzzle and Games, a woman-owned board game and toy shop based in Washington, D.C. that tries to avoid the stigma of the game store by emphasizing an all-ages, family-friendly environment. Labyrinth hosts after-school board game programs for K-12 students and donates money and educational games to local schools.

At my first tournament there, I walked into a warmly-lit space with pastel blue walls, and was welcomed by employees that directed me to the play area. The staff and event organizers kicked off the tournament with some basic ground rules: Play nice. The event space is right next to the store's kids section so attendees should use no language stronger than "butt" or "fart". Have fun! It's a small ruleset, but even that much feels conscientious and thoughtful. Labyrinth's store owner Kathleen Donahue says, “A lot of game stores lately have been saying they’ve been posting their rules on the walls. Our players kind of police themselves.”

Even so, Donahue and her staff enforce a safe space, stepping in when they encounter hostile and abusive behavior. “If someone is a jerk I kick them out,” Donahue says. She cites incidents ranging from racist jokes to a player banging on tables during a losing streak. “When I bring on a new hire, I explain the concept of the store to them. We talk a lot about the history of the store. Generally, I try to hire people who have some sense of acceptance.”

The Labyrinth’s Netrunner events I’ve attended tend to draw 16-24 participants on average, and amongst them, 2-4 women and 3-4 non-white players. My friends from other parts of North America tell me those are great numbers in comparison to their local scenes, and then we’re all sad that we those are considered relatively strong numbers. I’ve been relatively lucky with my local events, and hearing experiences like Peters and Brice’s only reminds me of how much work there’s still to be done.

In the discussion on increasing the Netrunner’s community’s diversity, I find we talk a lot about why there aren’t more women in the game, and not much on the lack of people of color. With this in mind I reached out to Hollis Eacho, one of the few black players in Netrunner’s competitive circles.

Like me, Eacho started his teens with the Pokémon TCG, but his interest in gaming became more tech-oriented as he got into video games and LAN parties in high school. He believes that it was this interest that led to his career as a technical sales supervisor at a web hosting company, as well as his interest in cyberpunk and Netrunner, a passion that took him to 2014’s world championship as a competitor.

In both his career and Netrunner experience, he finds himself one of the few black members of those spaces, and he believes that the real tech world affects those who partake in a fictionalized version. Eacho says, “If the [tech] field is primarily dominated by white men, I would expect a game that is heavily embedded with things in that field, also appeals to the same demographic as the people who are in that field.” He also believes that technology is growing as a universal element of people’s lives, and applauds the Netrunner vision of the future that subverts current tech culture demographics to feature a better balance of genders and races.

Geordie Tait, a prominent figure within the Magic community, once wrote about why people of color may be less visible within that game, and much of his reasoning can be applied to Netrunner. He cites statistics on the income disparity between white, Hispanic, and African-American households and the fact that Magic is an expensive hobby dominated by the people who can afford it. It features a card pool with varying tiers of rarity, predominantly sold in randomized packs. To become competitive and create stronger decks, players must buy more of these packs in the hopes of striking probability gold and acquiring better cards, or pay extra to buy individual cards on a secondary market like eBay or Craigslist.

In contrast, Netrunner operates on a “living card game” model that has no randomized card sets, so there’s theoretically no such thing as rarity and all cards should cost the same. Real talk, though, at this time of writing, this is approximately what a Netrunner collection looks like: 2-3 core sets ($40 each), 3 deluxe expansions ($30 each), and 22 monthly smaller expansions ($15 each) -- and counting, as new cards are released regularly. For players that own complete sets and keep up with the regular new card releases, this amounts to a fairly significant chunk of change. Even beyond the actual price of Netrunner, the pricing structure of older collectible card games have established the genre as a hobby that Tait compares to stamp-collecting, “unruffled by its exclusion of the poor.”

Fantasy Flight Games’ 2015 Worlds Championship has sold out. The fan-run pro circuit features 33 events across the US. Interest in high-level play is strong, but there’s an increasing anxiety over who is being left behind as the community grows. D’Argenio and other organizers of the ANRPC are active on forums and produce online streams of play, working towards greater visibility and outreach to players worldwide. Still, most of the women players I talk to avoid online community spaces, having been already burned by other forums or having little interest in popular discussions of rules minutiae.

I’ve found that a lot of the outreach work has to happen at low stakes in-person events. For example, when Peters emailed the tournament organizer about her negative experience, he apologized and invited her to attend his next event, one created specifically for those new to the tournament scene and again had reserved extra tickets for women.

At the beginners tournament, four other women joined Peters in attendance, and she encountered a much more relaxed atmosphere. "I know he sent out a 'Feminism 101' email before that tournament," Peters said. “I don’t know if it was that or the fact that it was for beginners, but it was definitely easier and everyone seemed more nervous, therefore more friendly.” She believes that other events would benefit from a similar education on microaggressions beforehand.

Brice would like to see more ways to play Netrunner that aren’t so tournament-oriented. “Even just casual play is a kind of store event that is newbie-friendly,” she says. She also suggests events that allow players to compete without buying many cards. “Having things that are constrained and casual and not meant to be getting you better for the tournaments, like only using core decks or only using [certain] packs would be great.”

There’s a sense that, despite tournaments being in-person play events, they are not conducive to socializing. Their scheduling leaves little time to speak to non-opponents, and all components revolve around competition. Brice says that at Netrunner events, “I want to get to know people. I want to have a conversation with them, I want to eat and drink or something. Just something that looks like other social happenings.”

Charlene Putney organized a Netrunner play event at the GameCity Festival in Nottingham, England, and chose a pub over a game store for her venue as she found it an easier space to play as a woman. She says, “At a pub, it’s very open. It’s very casual. You can pop in, and pop out—people aren’t going to look at you coming and out of the pub. You’re just another customer. You’re there with your friends or people you’re going to meet.”

Quintin Smith, a co-founder of board game site Shut Up & Sit Down, organized the two tournaments Peters attended and continues to work towards changing what the world of organized play looks like. In other events, he’s encouraged coming in costume, featured live DJs, and started an inter-city friendly series that required regional teams to play a variety of deck types. Smith says, “We were talking about how to keep the Netrunner community nice. I think one of the ways to do that is... friendly tournaments for prestige, for jokes, and for fun. Tournaments just because. Playing Netrunner just because.”

Netrunner’s designers have already put in the work in creating a future that stars people of all ages, color, and personalities. We can’t just pay lip service to being a different community, expecting the game’s storytelling to create a diverse play environment. Community leaders have to put in comparable efforts to reach out to those who don’t share their experiences, people who are alienated by the current environment.

Peters says, “If you aren’t attracting women and people of color, then you really have to ask yourself why. It’s simple as that. If they’re not there, then something is going wrong somewhere, as far as I’m concerned.”

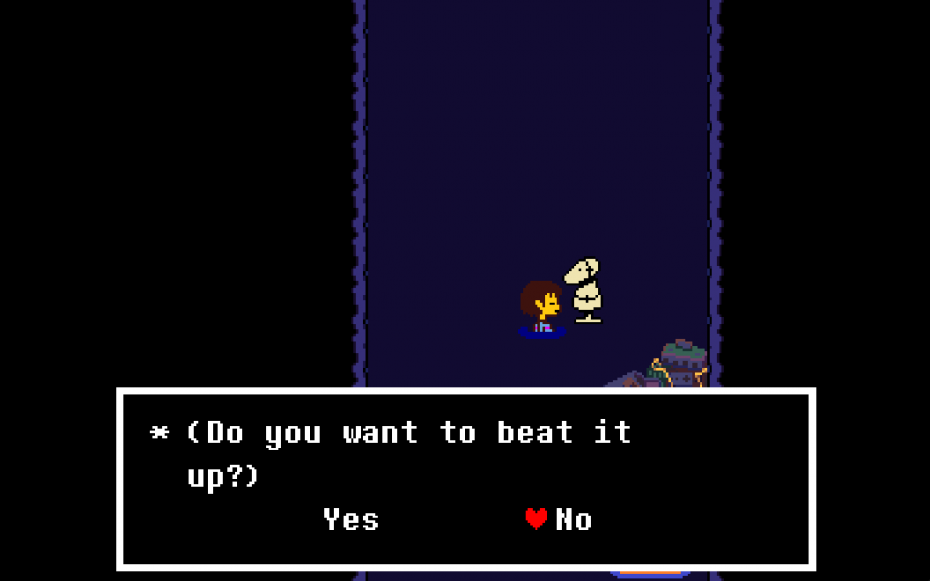

About halfway into our journey through Coda's games, they start to take a darker and more disturbing turn. Wreden decides that his friend is "in trouble," and that he needs to step in and "fix" the problem, but ends up committing a breach of trust so profound that Coda ends the friendship and cuts all ties. And thus we learn the "real" reason Wreden is making this game at all: He wants to reach out to Coda and ask him for forgiveness, even though he knows he's betraying Coda's wishes even more deeply by doing so.

About halfway into our journey through Coda's games, they start to take a darker and more disturbing turn. Wreden decides that his friend is "in trouble," and that he needs to step in and "fix" the problem, but ends up committing a breach of trust so profound that Coda ends the friendship and cuts all ties. And thus we learn the "real" reason Wreden is making this game at all: He wants to reach out to Coda and ask him for forgiveness, even though he knows he's betraying Coda's wishes even more deeply by doing so.