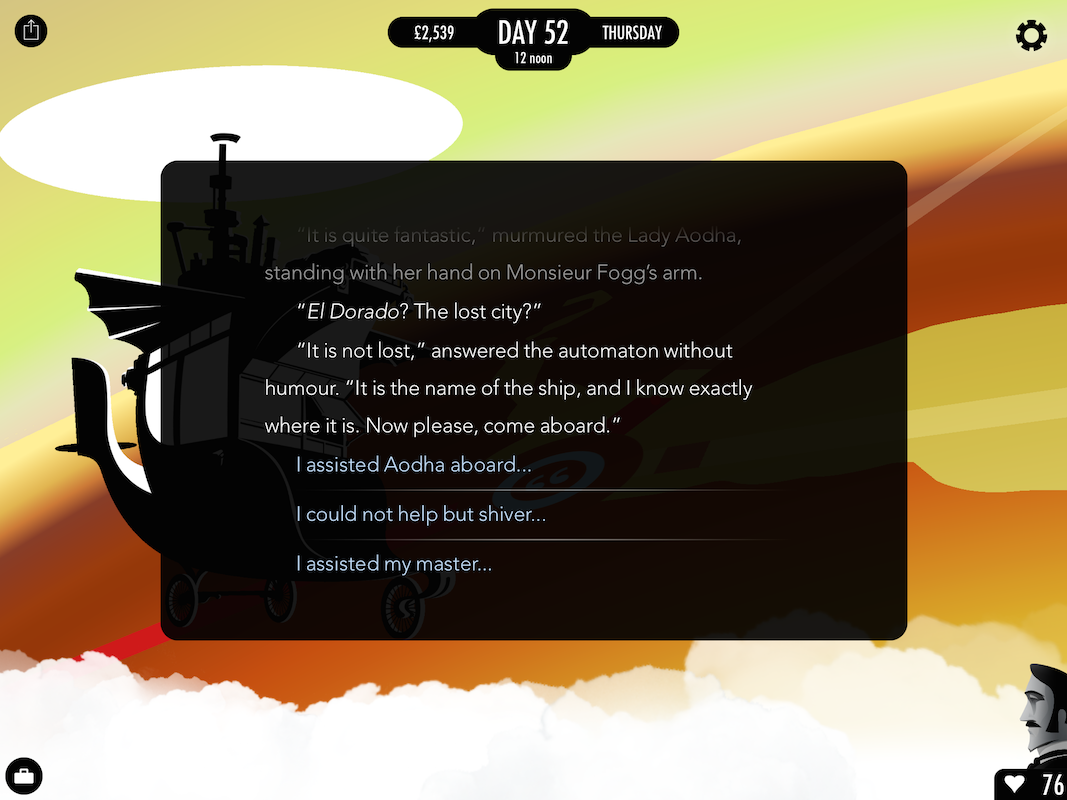

80 Days is a game based on the Jules Verne novel Around the World in 80 Days, but with a significant steampunk—and anti-colonial—twist. You play Phileas Fogg’s valet, Jean Passepartout, who must not only plan the sometimes-complex logistics of the journey, but ensure his master's well-being along the way.

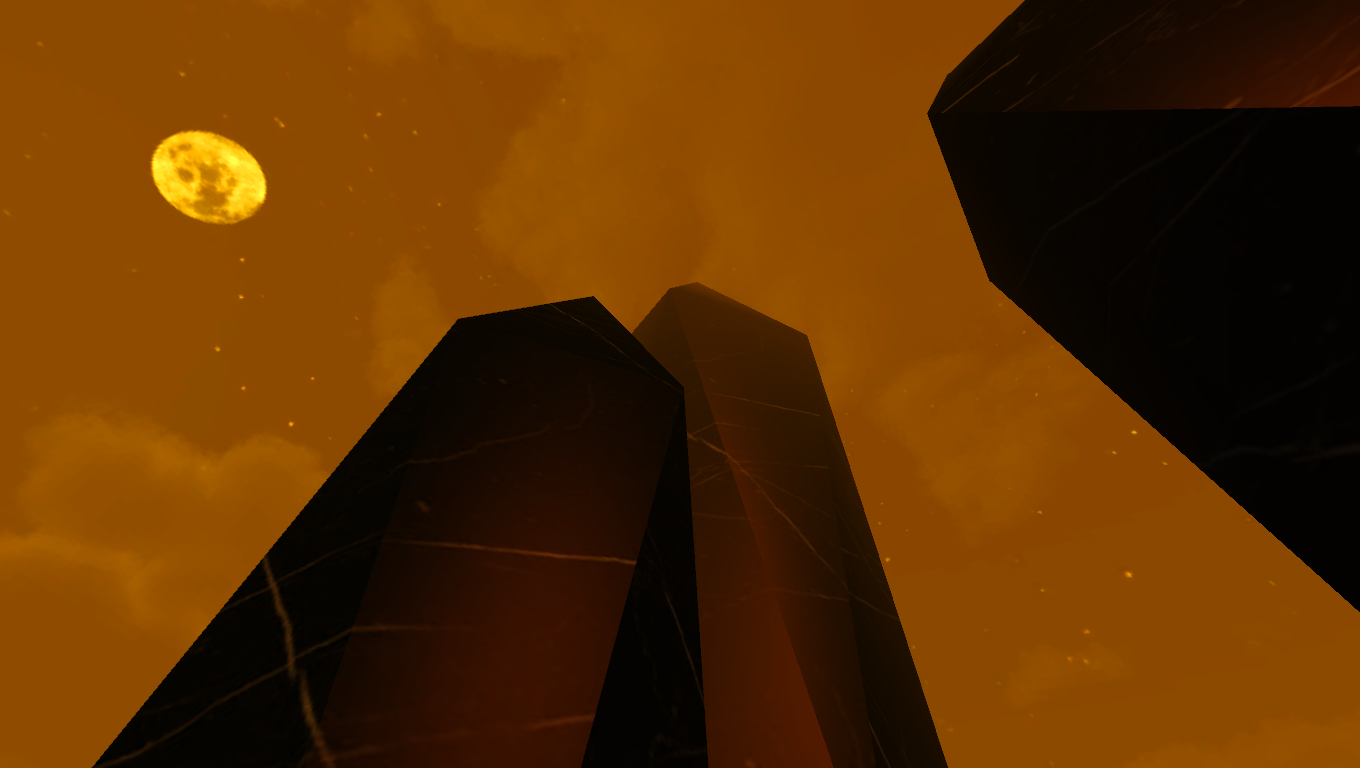

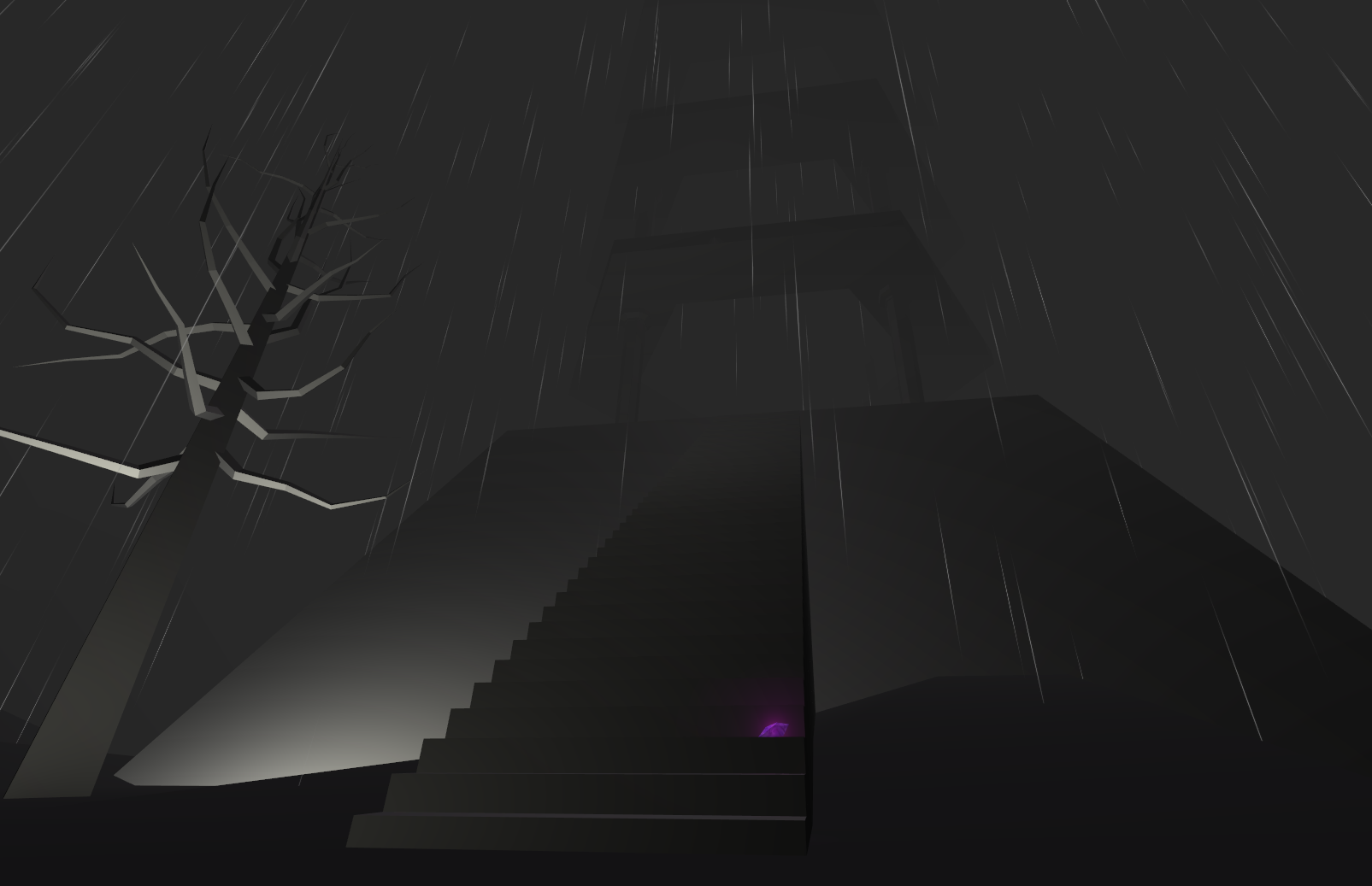

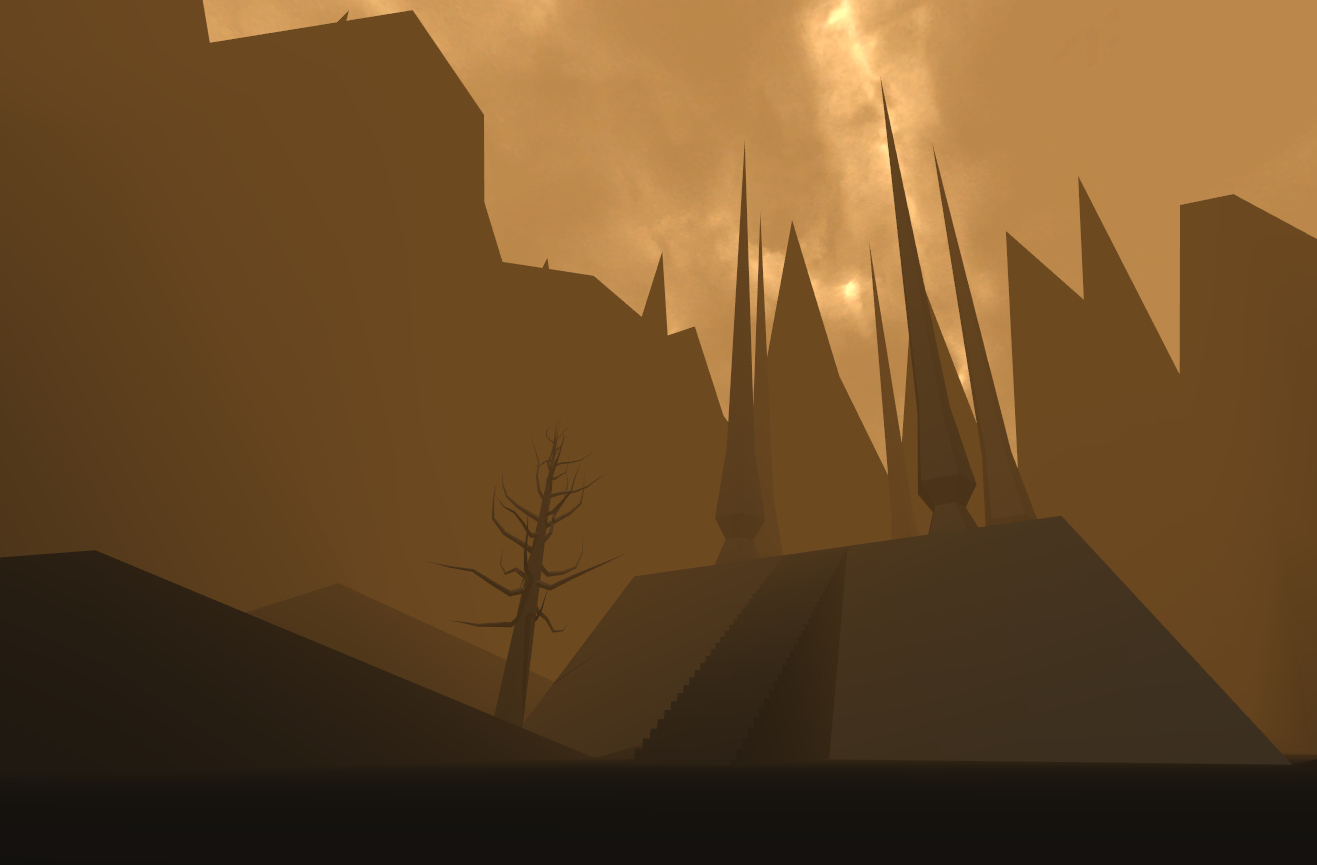

The graphics and aesthetic of the game are beautiful; they light sepia-tinted fires to the imagination as one plays, and act as gentle companions to the core act of reading, managing income and inventory, and making choices about how to travel and what to do along the way. But it’s the writing by Meg Jayanth, with a few stories added by director Jon Ingold, that makes 80Days game so memorable and more-ish.

While Jayanth loved the original Verne tale, she says she found his portrayal of Aouda, an Indian princess, to be “infuriating.” Treated like a “conquered territory” and a “prize for Fogg,” the character of Aouda evoked everything wrong with white European portrayals of non-white women in colonized countries. If Jayanth was going to try her hand at rewriting this classic tale, there would have to be an answer to Aouda.

In the process she wound up writing a hundred.

80 Days became a steampunk world where technology was both magical and political, where maps were dramatically redrawn, and where non-white people and women alike had scores of characters expressing a variety of views about this volatile world. Whereas the original Verne tale never left the British Empire, here the boundaries of Victoria’s kingdom are reduced, Asian and African empires have more robustly resisted European colonialism (while perpetrating abuses of their own), and Fogg and Passepartout must go well beyond their comfort zone and the protection of Her Majesty to complete their journey.

When the game first released on iOS, it became an instant classic—interactive fiction games often resist penetrating broader game audiences, but the tablet-friendly beauty and readability of 80Days earned it acclaim in many circles, and multiple media awards. Now the game comes to digital download platform Steam, and with that release comes a brand-new expansion to the game: Canada, the US, and South America have more cities to visit and many more people to talk to—especially Natives, who Jayanth felt got short shrift in the original script.

“To be honest,” she tells us, “the lack of proper representation of native peoples in North America really bothered me when we first released—there are some in the U.S., but not nearly enough. It was always a goal to cover more of Canada and the US, and include more native peoples, but in the end I really didn't want to go in without proper research and time to get to grips with the history.”

The result of that research—writ large in all of Jayanth’s stories throughout 80 Days—is an impressive alternate history of Native North America and a bevy of new and interesting characters.

Assimilationist compromise and vibrant resistance are portrayed in equal measure and with sympathy. A mixed-race gyrocopter pilot who believes the past should be left behind; the Blackfoot Confederacy’s ownership of the Canadian Pacific Railway through creative treaty negotiations; a floating city where pan-Native resistance to settler colonialism rules the day, a proud Native woman Mountie; all have their say and make their mark in Jayanth’s lush prose. The nature of narrative fiction is such that it allows for such capacious characterization, where finely honed descriptions and dialogue can fill in vast spaces that advanced graphics cannot even begin to render. Jayanth extends the quiet triumph of her writing here: she portrays people of color as diverse unto themselves, with different politics and ways of engaging the world.

It’s not just a breath of fresh air, but a whole climate thereof in a medium where we’re used to seeing maybe one character of color burdened with representing their people. Instead Jayanth gives us credible snapshots of civilizations.

The new content pops up all over the globe, but is concentrated primarily in the Americas, where several new routes across its vast terrain have been added, along with a bevy of new characters for Fogg and Passepartout to bump into. It really is more of everything I loved in the original; more dashing, muscular women piloting airships, more clockwork dreams come to life, more transcontinental train journeys, more humanizing speculative fiction.

The Native American and First Nations characters are carefully and elegantly written, many identified by tribe and with various languages represented faithfully; they’re active, diverse, credible participants in this volatile world of brass and steam. This is a throughline of the game: exploring what travel technology means to a crowd of characters from around the globe.

It was a tone that had already been set by the game’s last update, which added the North Pole and a lot of lore about Arctic native peoples. Qausuittuq, a secret city at the Pole, “was founded for one purpose—for the Circumpolar peoples to learn and develop the technologies of steam and oil and automata. To make them our own, before they destroy our homes, our culture, our way of life,” in the powerful words of Ráijá Juho, a Sami engineer.

The new content extends that beautiful conceit down into Canada and the U.S. In addition to making this world’s wondrous technology their own, Native people here militate with stereotypes—alcohol comes up a lot, but primarily as an indictment of settlers. In one fascinating scene, Passepartout and Fogg are mistaken for whiskey traders by a First Nations woman and dealt with appropriately. Meanwhile, the Blackfoot Confederacy leverages its majority stake in the Canadian Pacific to banish alcohol and tobacco from their trains. Others pilot airships or gyrocopters, others convert to Christianity or act as translators for the settlers.

In short: they’re human.

But it’s the way Jayanth weaves this humanity into the fantastical fiction of 80 Days’ steampunk world that really sells the whole thing. My favorite addition to the game has to be Kahwoka Othunwe, the Floating Village: imagine a free Native city held aloft and steered by a rainbow of balloons and dirigibles, where the Sioux, Cree, and Iroquois nations came together to create both policy and foment anti-colonial resistance in secret, their existence confirmed only by rumor and tall-tales.

It’s another wonder that humbles Passepartout and Fogg on their travels. “We are a spark of defiance,” Winona Fire Thunder, an Oglala Lakota tribeswoman, says of Kahwoka Othunwe to her white visitors, “A story to be told in the dark, when all hope seems lost.”

In that moment, my tablet became a candle in the night.

In reviewing the expansion, I tried to take paths that I knew would lead through the new content, but I hit a snag in the form of the game’s best feature.

You see, it can be surprisingly challenging to commit to a specific path in the game. With most cities acting as forks in your long road, the call of adventure, to skip out on your own itinerary, is difficult to resist. I resolve to take the Trans-Siberian Railway and yet find myself on a ferry to Helsinki, and thence to the North Pole. Why? Perhaps breaking one’s own rules is what freedom looks like; often in my real-life travels I’ve wanted to hop off to some other far-flung locale in lieu of returning home. 80 Days lets your spontaneity run wild on primitive cars, majestic ships, dinghies, dirigibles, hovercraft, trains of every vintage, and all modes of transport in between.

Last week, in reviewing Wheels of Aurelia, Leigh Alexander wrote about the particular way women experience the freedom of driving; in a curious way, 80 Days does the same thing for us with almost every other form of transport. Though the game centers on the journey of two men, and does so staggeringly well, the lavish stories that vivify the many women they meet on their travels makes it easy for me to identify with them—especially those that accompany Fogg and Passepartout for a few days or more.

There are a number of examples I could cite from the game’s spiderweb storylines, of mighty travelling women for whom a ship or a balloon or a motorcar is a means of escape and survival. But one story, written by Jon Ingold and new to this update, stands out brightly.

If luck is with you and you find yourself a tad adventurous, you might find yourself in the company of The Black Rose, a nonpareil jewel thief who sets her sights on the mightiest prize this world has to offer. You can catch a fleeting glimpse of her on a train, shove her away from your company for the pleasure of Monsieur Fogg, or make a boon companion of her to travel the world with. The latter option will not disappoint.

For women, especially queer people and women of color, travel is the essence of precarity; it is purposeful, with each mile potentially being our last. Mission weaves a curious helix with spontaneity and adventure; travel washes away our pasts and gives us the illusion of actually being the machines that convey us to far flung destinations. The Black Rose, an elegant and cunning figure embodies this perfectly; she is the only other person in the game who travels as far and wide as Passepartout and Fogg, and who keeps up with the brisk pace of their journey.

You may find, as I did, that her purpose and her longing for the freedom of the open skies makes for much better companion than the dour Englishman who initiated this journey.

I related to her in an odd way; escaping from a hardscrabble upbringing through travel and practised elegance. What else could I do but spread my wings and take flight with her?

“When I look at playable women of color in games now I have more hope, but I still cringe at the characters that fall back on old racist stereotypes and add things like

“When I look at playable women of color in games now I have more hope, but I still cringe at the characters that fall back on old racist stereotypes and add things like